melhammond.com.au

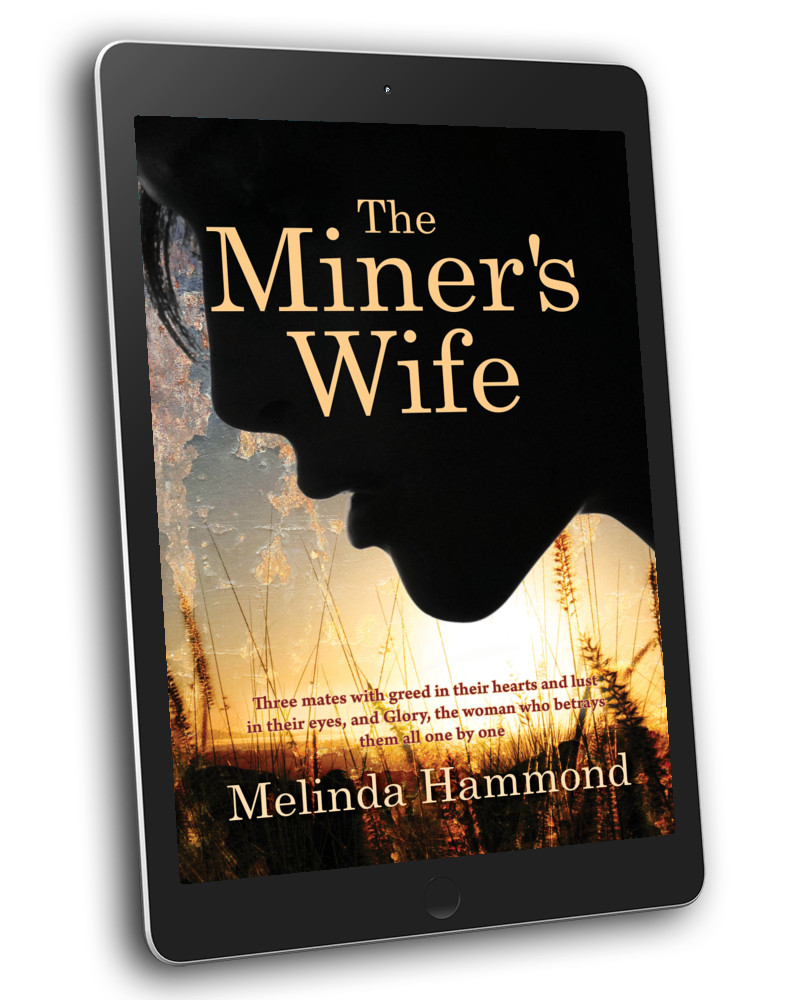

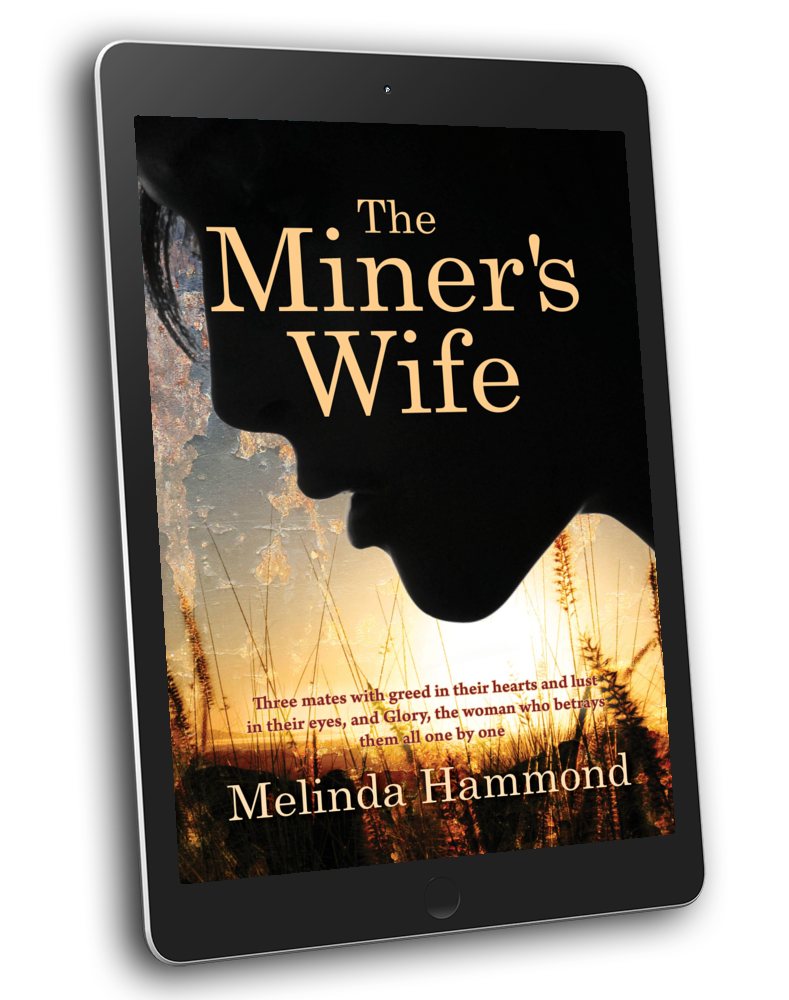

The Miner's Wife - EBook

The Miner's Wife - EBook

Couldn't load pickup availability

She stands out at first, blond, pretty and fresh, setting out from the city, full of hope, wanderlust and adventure. She paints her name on a rock at the Dundas in capitals, and then opts for two kids and husband with a good pay packet. Glory is on a downward spiral to insanity. She is a mining wife in a mining town in the middle of nowhere, on a road fallen off the edge of the Nullarbor, where dead men tell no lies. Glory and the three men who love her - one dead, one silent, and the third is back to collect the gold he left behind. Three mates with greed in their hearts and lust in their eyes. Glory, the woman who inspires them all, then betrays them one by one

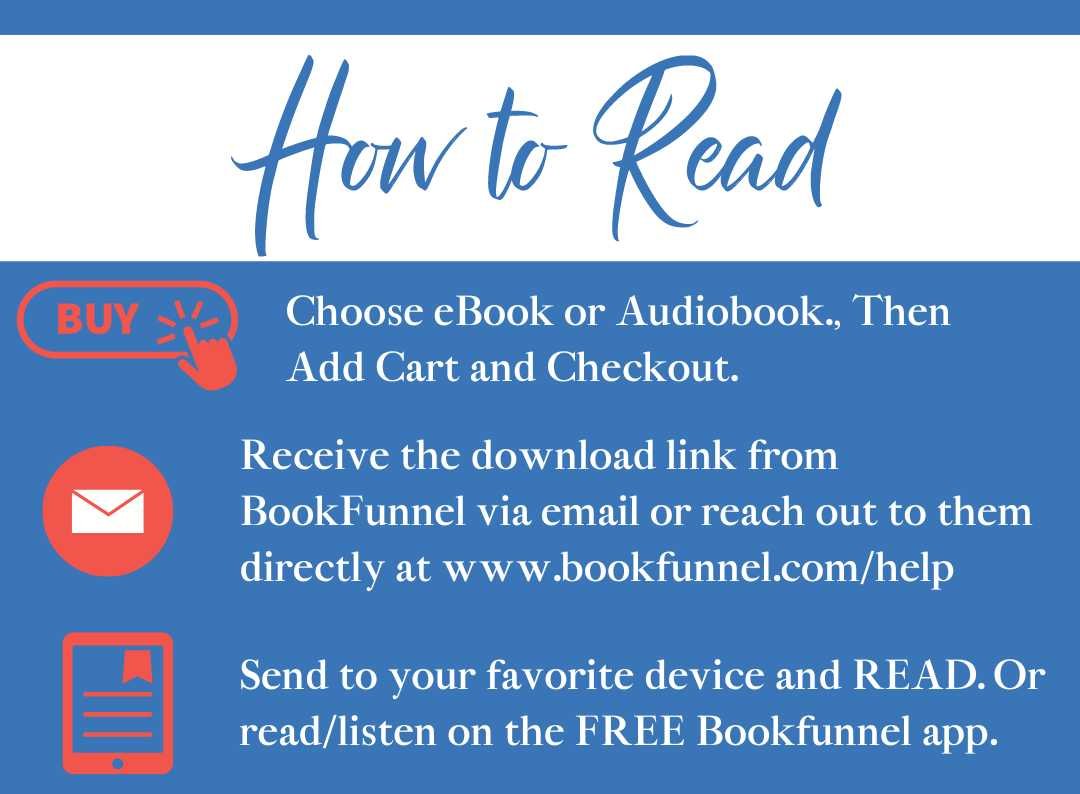

THIS EBOOK WILL BE DELIVERED INSTANTLY BY EMAIL by BOOKFUNNEL

OR YOU CAN BUY IT THROUGH YOUR FAVOURITE ONLINE BOOKSTORE

______________________________

CHAPTER ONE

Thus…I plodded in the salt, and the rising moon found us plodding in the half-boggy track. Shadows of islands came and went, and were distinct and then blurred as our footsteps fell soundlessly on the salt – the ghosts of men and feet on the ghost of a once great sea.

Randolph Bedford, 1984

Crossing the causeway into town is supposed to be a special moment for JJ Reddy, to measure the time passed, the years slipped by, but instead his gaze is drawn to the BP Roadhouse at the T-junction of the Nullarbor, with Kalgoorlie one way, and Esperance the other.

Several of the fluorescent bulbs on the B are blown, a small thing that in the city would have passed unnoticed as he wandered along Subiaco Road in search of a Crownie and a familiar face. Out here the BP is like him, an intruder, suffering at the hands of a careless manager more interested in the dank anonymity of a corner booth at the back of the cafeteria¾with his long cold cappuccinos and burnt to the stub Holiday 8’s¾than in the appearance of the only real choice of refreshment for hundreds of miles, and already the roadhouse blends into its surroundings with weary acceptance, like it has always been.

As the coach pulls into the dim lights of the parking bay JJ is tempted to light up a cigarette like all the other passengers, order a burger to go, and cue for a piss while he waits for his order to be filled. Instead, he steps to one side and waits while the driver unloads his gear¾one pack, hastily crammed with clothes to last him a week, or forever, whichever comes first.

Either way, he has everything he needs.

JJ knew the phone call was going to be bad. His clock stuck on midnight, the luminous red numbers flashing at him, signalling another power failure that sends his video, TV and clock radio into flickering raptures. Only this time he doesn’t wander around half asleep, reordering his life as he reprograms his electronics. This time he is going home on the Number 93 coach.

It takes him until dawn to decide what to pack; toothbrush, t-shirt, change of underwear, razor and his Nikon. Company issue will take care of the rest. A phone call to the editor of National Geographic, he pitches his proposal, The Legend of the Salt Lakes. Just another photo-shoot. Only this time he will be subject.

Immortalised.

Sucked into the vortex of the salt lakes and left to rot in family tradition.

Funny, it had been his mother who had encouraged him to get out. Follow your dreams, she had said in clichéd monotone, mimicking the voice on Radio National that is never far from her ear. The same voice that orders the death of his dreams on the midnight clock.

For Araluen.

She has made the call for Araluen.

And he is the sacrifice. He is the man. It is his duty to carry the burden.

When he shuts the door of his Subiaco flat, he leaves the radio on. It is a ritual, a welcoming committee of noise for a returning warrior.

He doesn’t blame his mother. She is of that generation. ‘Please son, I need you.’

And he came.

Lake Cowan¾number nine in the guidebook¾stands guard over the mining town of Norseman. To enter, cross the causeway. Not the original causeway, marked by the intersecting overland telegraph lines of Coolgardie, Esperance and Euccla, the causeway nobody knows about. The causeway not in the guidebook.

Like the aboriginal graves behind the ridge.

Unmarked.

Sacred and secret.

Like the salt lakes shimmering with the bones of dead men buried with their dreams.

A miner was killed in the mine today. Jackson Reddy of Norseman, underground drill operator, died instantly, may he rest in peace.

Kalgoorlie Miner

15 August, 1977.

But dead men don’t rest. They live out on the lakes and take their chances. Dead men talking. JJ knows because he’s been hearing them since he was a kid. Seeing them bounce shadows off the moonlight. Moonlight and salt lakes. Should make a good photo-shoot.

Dead men waking.

Welcome home, Son.

Welcome home.

BP bus stop, Norseman, turn left to freedom or get off now. JJ reaches for his pack, dumped to the ground by the driver who is already striding towards the idea of a hot coffee and a steak sandwich, his departing passenger already forgotten in the routine of his day.

JJ swings the pack over his shoulder and turns away from the servo and the opportunity it offers to pass through this place with nothing more than a piss and a feed. He settles the pack more comfortably and begins the long walk into town.

He is home and freedom is not his to choose.

‘Hi JJ, what you doing back? Ain’t seen you round since your old man died.’ JJ has barely made it to the end of the servo’s driveway before he is greeted by the squeal of tyres and a long familiar voice. He leans his elbows against the driver’s window. ‘Well, you’re seeing me now, Shiner.’

‘Ain’t changed none, have ya?’ Shiner grins. ‘Still looking for me to give it to ya.’

‘Still waiting for you to try. Any chance of a lift into town?’ At his old friend’s nod, JJ slings his pack into the back of the ute and climbs into the passenger’s seat.

The trip into town is short and JJ closes his eyes to the sight of the place he is not yet ready to see. But he sees it in his mind anyway; the main street wide enough to swing a camel team and the roofline of tin buildings that has held its shape for a hundred years, unmarred by McDonald’s neon glow, the smooth ripples of corrugated iron stretched end to end. Horizontal strips meld together to make up houses. Homes. Rough-hewn, pioneer-made.

They came, they stayed. Generation after generation lining the walls in photographic splendour. Stiff portraits boasting cherubic children, with tall proud fathers in cambric shirts and mothers in starched lace, hands clasped tightly on exhausted laps, staring grimly at the camera.

Gold. Gold fever. Gold dust. Dreams that brought men to the West. Pioneering. Adventure. Riches beyond imagination, a never-ending line from the Ballarat diggings to the West Australian goldfields. Women and kids, dependent, deserted, soon forgotten. Heroes in wagons. Walking. Opening up the vast interior, enduring hunger and thirst, captured on canvas by Sydney Nolan and sold for thousands. A hostile land.

They came from everywhere to strike it lucky, strike it rich. Filled with a hunger for gold. A man can disappear out here. He can start afresh or just keep on moving.

The old township in panorama in the council foyer showing proud days of bustling activity. Mining camp to tent-city; the council decrees constructions of timber within the town’s limits, no dumping of garbage, no parking camels on the footpath, no drinking on Sundays. The romance; a town in its heyday with all its dramas and robberies, colour and life, a place to read about over Sunday brunch, then turn the page.

Come to Norseman, back to Norseman, a trip to Nostalgia, come with me, trust me. Photos to cement the lies. Escape while you can. Booming town, mining town, slow dying town.

Row after row of Company houses boxed in neat Leggo lines. A frontier town with a three-year mine life living on Company rations. Lawns. Women queuing at the hardware store for Iceberg Roses. Civilisation. A mining town struggling forward, feeling guilty for not dying years ago. A town waiting in resigned acceptance.

Population 1500 and a horse called Norseman. Gold panning, gold tours. They’d tried. God, how they’d tried. But you can’t beat the bottom line. Bitterness, resentment and resignation all on Company issue. JJ wants to block it out but he can’t. A persistent tug of memory calls this place home.

When he finally opens his eyes the only difference he sees is the clock, standing sentinel in the middle of the street, shaped like a head-frame and stopped dead on midnight. JJ knows it is a welcome home gesture from the salt lake boys.

‘Hey, dreamer,’ Shiner bruises JJ’s ribs in friendly invitation. ‘I said come for a beer.’

It’s seven o’clock in the morning and change of shift. Shiner will knock back a few beers before he crashes in readiness for another twelve-hour stint down the big hole. A miner’s lot, JJ knows. Might as well get used to it.

‘Sure, why not? As long as you’re shouting.’

Shiner angle parks the ute alongside a dozen others out the front of the Railway Hotel. ‘You here for good this time?’

‘Nah,’ JJ spits the lie an easy distance. ‘You know me. Just passing through.’

‘Lotta people do that ‘round here.’ Matter-of-fact, Shiner sums up the transience of a mining town.

‘Could be because there’s only one road to take.’

‘You didn’t waste no time takin’ it.’

‘This town isn’t big enough for two of us.’

‘Least you got that right.’ Shiner’s words reverberate over the slamming of the ute’s door. ‘Your shout, city boy.’

As the daylight closes behind them JJ smells the stale leftovers of last night’s Chinese takeaway coupled with the rotting debris left by local teenagers attracted to the pub by the home grown band and the dope passed under the table. JJ eyes the dead-red carpet and the torn gold embossed wallpaper with a resigned sense of homecoming.

The long road out of Norseman leading full circle. The trip of a lifetime. Johns’ General Store and gobstoppers, five cents worth of mixed lollies. Him and Shiner, JJ can see them now, their dragster bikes flung carelessly in the gutter, noses pressed against Johns’ window, fiddling their twenty cent pieces in their pockets, calculating, whispering, and moving on. It was part of the ritual, they’d come back in their own good time, choose two cents worth of liquorice, two cobbers and a musk stick, spend the rest on Phantom comics, mount their dragsters, cross the railway line, pass the slime dump and head for the hills.

They had their special places but this day called for total privacy. March twenty-eight, 1977, seven hours since the big explosion, and the boys were yet to talk about it. JJ looked at Shiner, whose gaze slid away, Shiner at JJ, who suddenly found the slime dump fascinating. They pedalled across the haul road, and climbed Ajax Hill. There was no fear of concealed mine shafts—dangerous, and to be avoided, said their mothers sternly—merely great launch pads for wheelies. Secrets to tell, secrets to hide, the landscape whispered its secrets on lonely winds.

JJ was eight years old when someone blew up the courthouse; the colours brighter than the desert sky at night; the bang louder than twenty kilos of Power Gel set as a single charge. He was just a kid watching the fun with the rest of the town. It wasn’t until twenty years later that he thought to ask why.

It’s part of the folklore. Everyone knows who did it, but no one is saying for sure. The melted pile of metal that was the courthouse typewriter stands in the museum as testimony to the night. They found it on the roof of the post office a block away. But what would you expect in a mining town. They knew how to set a detonator all right.

Kaboom!

As kids they had found it romantic. They climbed Ajax Hill and acted out the bang again and again. Bang after fabulous bang. They made model courthouses galore and sent each one scattering in the wind with explosion after explosion, the louder the better. But it’s only now that JJ suspects the truth. The battery on Mines Road, night shift, the occasional truck taking a detour from the haul road. Ore not quite weighing in right. Miners with ti-tree farms in New South Wales. Blowing up the evidence. Cops doing their stint on the big block catching petty crims as they fall off the edge of the Nullarbor. Hearing the explosion and shaking their heads.

They still laugh about it in the pub. It’s a myth, a local legend, something to break the monotony of a twelve-hour shift down the big hole, and they’re glad to talk conspiracy with JJ. After all, he’s born and bred of a miner’s blood.

JJ doesn’t want to know, yet he feels compelled to listen. He knows the truth isn’t worth the risk but he waits to be told. He could just have closed his eyes. JJ knew who was there that night, who was missing, and why. He remembered the boom, and running, and a fire. The day after was the mess to admire. To him it had just been exciting. Kaleidoscopic colours: reds and exploding yellows. He remembered people’s faces. Him and Shiner scooting round the back, a pair of boys intent on innocent mischief. He saw again what they had seen.

Forgetting had been easy. Twenty years of a rich kid’s life had done the rest. But at the BP on his first day back he sees it in Shiner’s eyes. Shiner, a grown man, a mining man, and a family man—four brats and a blonde looker called Sal for a wife—and proud of it. For all JJ knows his old school friend has investments in tree planting schemes in Port Stephens.

‘Can get you on at the mine, mate.’

‘Thanks.’

A grin. ‘Another one you owe me. So what really brings you back?’

JJ looks at him and Shiner groans.

‘Don’t go there, mate.’ A warning couched in friendly concern.

‘Got to, eventually.’

‘Who told you that? Better forgotten, I reckon.’

‘Shiner, we know.’

‘Wrong. We saw some shit and made up the rest. We were kids, what did we know?’

JJ pauses underneath the string-bare chandelier in the darkened hallway of the pub that casts shadows up the wooden stairs to the rooms above. JJ has fond memories of lost virginity up those stairs, not that stairs were an option in his day. It was the up the drainpipe and join the queue. Twenty bucks a throw for a go at the local skimpy. Took up all his birthday present money for ten years. Jennie the skimpy. She’d cleaned every local boy in town out of his birthday money, a hundred years of happy birthdays in total.

She’d be twenty-six now, with saggy tits and a worn out pussy. Maybe she’d taken the money like she’d planned and ran. Or maybe her dreams are out there on the salt lakes with the rest.

JJ doesn’t want to know but he asks anyway. ‘What happened to her?’

Shiner acknowledges the memory with a wink. ‘Knocked up by Mikey Smith. She grabbed him by the dick and didn’t let go. They’re at Roxby now. Four kids.’

A dream come true. Respectability worn with weary pride. He closes the memory and heads for the silent row of drinkers at the bar.

Shiner takes his position alongside JJ, and tosses their order with careless jocularity, ‘Hey, little sister, a beer for the city boy and the usual for me.’

Shiner’s grin, a fifteen year-old’s grin, foreshadows the joke that is to come, the joke that JJ isn’t even aware is on him until his eyes adjust to the dim light inside the bar. Only then does he acknowledge Shiner’s cunning. ‘Touché, bastard,’ he says without taking his gaze off the barmaid. ‘Hello, Lui.’

Araluen slides a beer into JJ’s hand. Araluen his sister. Araluen the skimpy. Araluen who meets his gaze with defiant ease.

Araluen up the drainpipe. Working her dream. Happy birthday kids.

‘Hello, JJ.’

His little sister, topless. Skimpy. Araluen Skimpy. His Sister Araluen Skimpy. Araluen Slut.

‘You done her, Shiner?’

‘Yep.’

‘How much.’

‘Fifty.’

Share